It has clocked up one thousand years, the venerable Strasbourg Cathedral, an age that truly deserves veneration. That’s what the European Studio Glass Art Association (ESGAA) thought and adopted the motto Lux Aeterna (Eternal Light) for its big art event this year, the Sixth International Glass Biennial. It draws the luminous line from tradition to modernism, from the stained-glass windows of the Cathedral to the more than sixty artists of the present, who visitors will be able to discover or rediscover at the numerous exhibitions and events.

The vitality of Strasbourg’s glass scene is due not least to Pasquine de Gignioux, a passionate art lover and gallery owner. As early as the 1980s she began to promote glass artists. She was also instrumental in setting up the glass department at the Strasbourg École supérieure des arts décoratifs (ESAD) at the Alsatian art and music college (HEAR: Haute école des arts du Rhin). When she became ill in 2003, two of her art-gallery clients, the collectors Laurent Schmoll and Marcel Burg, continued her work and founded, in view of the continuing reservations in France, the ESGAA in order to make glass as an art medium accessible to the public. Entirely in the spirit of Pasquine de Gignioux, the organizers are also interested in the exchange between the new generation of artists and their more experienced colleagues. For this area, they were also able to attract the renowned glass artist and former ESAD head, Michèle Perozeni, who herself had studied ceramics and glass at HEAR. Her successor since 2009 is Yeun-Kyung Kim, also a graduate of ESAD. On the occasion of the biennial Uta M. Klotz asked the two artists which developments glass education at the Strasbourg college has undergone in recent years and what its priorities are.

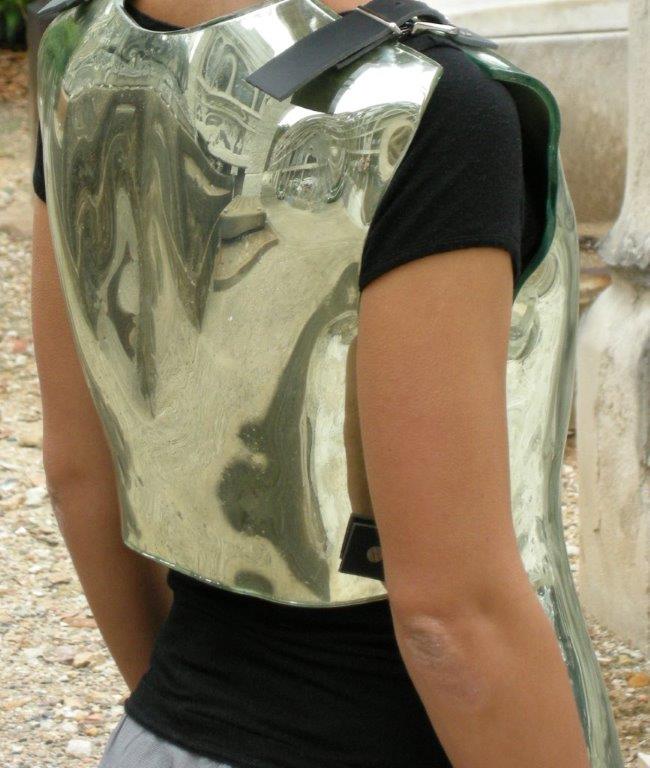

Pippa Beveridge: The Custodian of Memory, breastplate, float glass, cold-worked and silvered, leather, 65 x 35 x 25 cm

Michèle Perozeni: When the glass department was established at ESAD in 1985 as the last of the various courses of art studies, it was a historic breakthrough. Up till then no other art college in France offered glass studies. We set to work enthusiastically; the director at that time, the teachers, as well as the students were highly motivated. Their numbers continued to increase. As teacher I tried to instill that it is not just about glass for its own sake. Rather they should learn to move between two balanced poles: between their personal artistic development within contemporary art and commanding the necessary technical skills to go their own way in the end. In my opinion, it is important to find the right balance between creativity and technique, between educational guidance and Independence.

Naturally there were staff and structural changes at the college in the course of time. There was also the danger that the art courses would lose their autonomy and become simply service providers. As a consequence the departments positioned themselves anew: There emerged the area Option Objet (object option) with seven workshops (glass, jewelry, ceramics/earths, wood, metal, etc.) having a common comprehensive teaching concept.

UK: What happened when your former student Yeun-Kyung Kim took over your Position?

MP: A generational change brings about transformations. Also, Yeun-Kyung Kim came from a different culture. Beyond that, all artists who teach have their own history, their personal strengths and weaknesses. Our ideas about teaching are quite different. My approach to glass is closely linked to the inherent qualities of the material, its fluidity as well as solidity, and its many facets, at times poetic, at other times philosophic. Yeun-Kyung Kim proceeds in a more pragmatic, unconditional manner. She has a rich artistic vocabulary and is very confident in her handling of various materials such as glass, metal, textile, or plaster.

Hélène Launois (France): Méduse, 2013, lumières, verre, métal, objets aquatiques et Plexiglas, 180 x 140 x 35 cm, exposée à la galerie Frédéric Moisan, Paris, 2013

Yeun-Kyung Kim: When Michèle Perozeni was teaching, there was hardly any transition or permeability between the various courses. Students had to choose a specific major. But since 2009 the workshops are open; students no longer focus on a single subject. That development came from the students themselves because they wanted to learn to use the various materials. It also has to do with changes in society, however. Art colleges don’t stand outside of society; they are a part of social and cultural reality. Not all graduates become artists, so the teaching must be open. It is important to be flexible to work in art-related industries as well. That’s possible with the comprehensive teaching concept for the individual art-object areas. Certainly I have a different way of teaching than Michèle Perozeni; she has a completely different personality. I do try, however, to adopt some aspects of her teaching approach. I profited during my college years from her professionalism and enthusiasm and would like to pass on some of that to my students.

MP: In spite of the differences: What remains important is that we accompany students on their path with respect, that we listen and convey the subject matter in such a manner that students can acquire the greatest possible Independence.

UK: Many students at ESAD come from South Korea. How does the education there differ from that in France?

MP: In South Korea, art colleges are private institutions. Students have to pay for everything including the materials themselves. The subjects are compulsory and technologically oriented. The students gain excellent technical skills but make hardly any personal development. ESAD in Strasbourg is a state school, the materials are free of charge, the courses can be freely chosen, and the technical courses are optional. The goal is to sponsor the individual’s creativity. As a result students develop their own artistic expression within contemporary art, have less school-like teaching, and receive technical know-how adapted to their needs. For Koreans, who speak little about themselves, it takes time until they find their way into our culture. Yet they are receptive and pass on their technical expertise. They are an enrichment for all.

YKK: HEAR does not train glass technicians. Rather it is about glass as a medium and the ability of the individual to get involved with it. Those who want to can still attend a technical college later on. The first glass college in South Korea was founded Cheonan by a HEAR graduate in 1997. It has great resources and concentrates on the teaching of technique. Since 2002 there is a student exchange between Namseoul University and HEAR.

UK: Does today’s society actually still need something like art?

YKK: Artists are loners but they make it possible for others to cross borders; they show things beyond rules and norms. Even under the worst conditions people find the means and ways to sing, dance, paint, and write—to be. Eating and sleeping is normal; art shows the essential. We cannot do without art any more than we can do without freedom.

Uta M. Klotz conducted the interview, translated from French into German by Petra Reategui

Translated from German by Claudia Lupri

Verena Schatz (Austria): A Part of You, 2012, glass, stainless steel, flat Screen, camera, 60 x 200 x 8 cm